[All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

The Sheldon NWR sits on the Nevada side of the OR-NV border and is accessed by OR and NV Hwy 140. The Reserve is vast and home to antelope, big horn sheep, elk, deer, mountain lion, wild horses and burros that were set loose years ago. The Refuge Hot Springs was developed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930’s by building a wall on the low side of the hot spring runoff. The CCC built a shower house that is free and open to the public, fed by the hot spring water. There is a great free campground surrounding the pool. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

The road to the hot springs passes an active opal mine which offers tours in season. There is also an old homestead with a stone barn and a corral with a fence woven with willow branches.

It’s been my good fortune to enjoy the hospitality of my friends, Debbie and Liz, in Chimayo, NM, for the past nine years and be a guest in their adobe home along the Santa Cruz River. Their home adjoins the Malpais, i.e. the BLM badlands where I hiked many an hour. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

I’ve found many potsherds on the south facing slopes of this rock formation, typically with a white clay slip and black painted designs, but occasionally in red polychrome. The nearby Santa Cruz river would have provided water for the small settlement. The Jemez mountains are on the horizon.

There are many in this land that was part of Catholic Mexico until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 and The Gadsden Purchase of 1854 brought what is now part of Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona into the U.S.

The Santuario de Chimayo dates from 1816. It sits on the site of a natural spring believed to have healing properties by native people before the arrival of the Spanish. Since the early 1800’s the Catholic faithful have come here seeking miraculous cures. Over 300,000 from all over the world make the pilgrimage to the Santuario de Chimayo each year during Holy Week, many walking or even crawling on hands and knees from as far away as Santa Fe, NM.

[All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

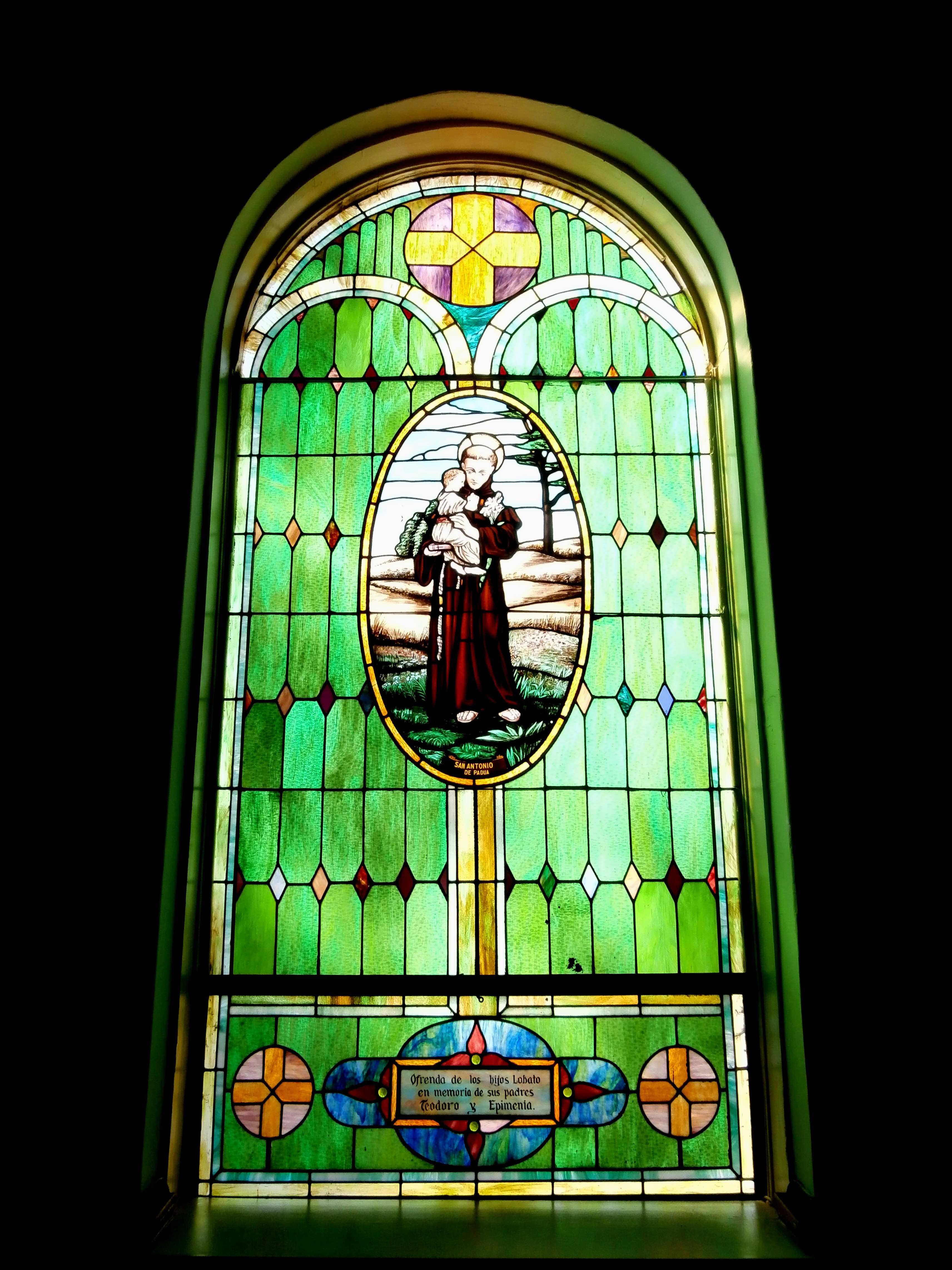

Present day Our Lady of Guadalupe church in Conejas, CO, known as the oldest Catholic church in Colorado, sits on the site of an 1863 adobe church. Spanish families with centuries of occupation in the San Luis Valley have endowed the church with beautiful stained glass windows, carved wooden stations of the cross, and a handmade altar, all made by local craftspeople.

The Sangre de Christo church sits on a high hill overlooking the tiny town of San Luis, CO. On the path up to the church are fourteen bronzes depicting the Catholic “stations of the cross” that were donated by a wealthy couple in Santa Fe, NM, who made the annual Easter pilgrimage to the church for 25 years.

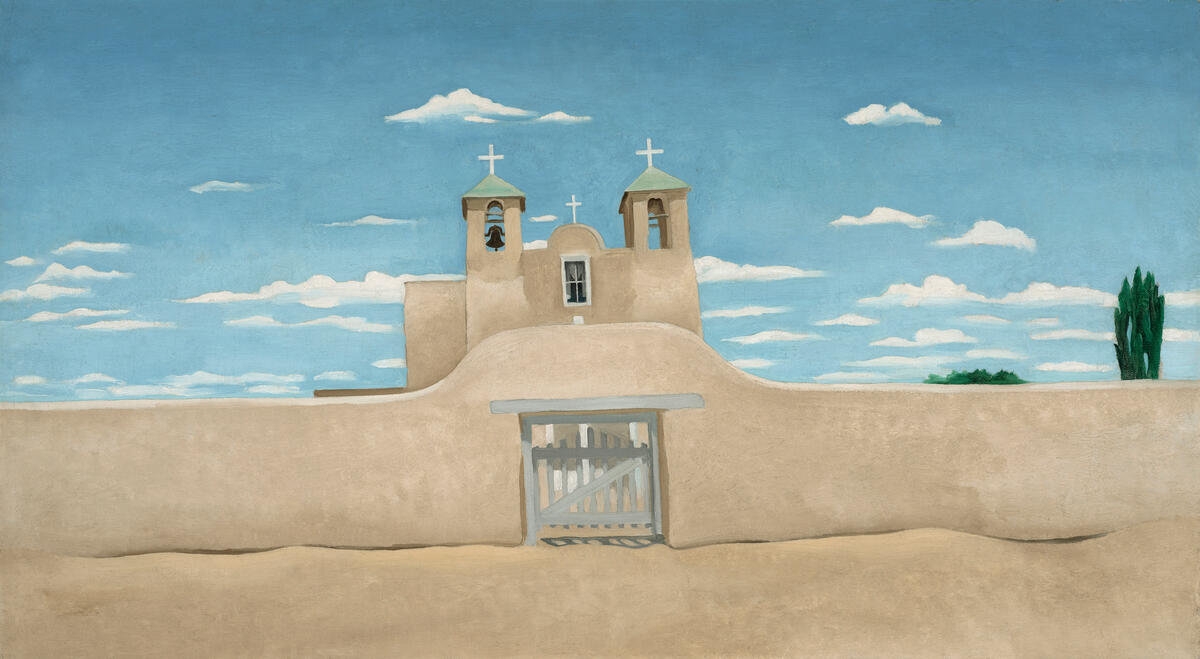

The San Francisco de Asis adobe church in Rancho de Taos, NM, was constructed between 1772 and 1816. It has become famous as the subject of several paintings from the 1930’s by Georgia O’Keefe. Two examples of O’Keefe’s depiction of the church, from the front and rear, are included following my photograph.

This is what it looks like on US Hwy 50, “The Loneliest Road in America” across Nevada. Actually, there are longer, emptier stretches elsewhere in the state. US Hwy 93 south from Majors Place to Pioche, NV, is one of them. The open road beckons. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

My brother, Terry, recently brought my attention back to a 25 mile stretch of highway, U.S. Route 550, from Silverton, CO, to Ouray, CO, that I traveled and photographed in the Fall of 2012. The name, Million Dollar Highway, refers to the rumored cost of $1,000,000 per mile to build it in the 1920’s when a dollar bought a lot more than it does now. https://thenatureseeker.com/million-dollar-highway/ [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

The route was originally surveyed and built as a wagon road in the 1880’s to carry incredibly rich silver ore from the Yankee Girl Mine located on the north slope of Red Mountain down to the smelter. While narrow gauge railroads were built to serve mines all over the Colorado Rockies in the late 19th century, defying gravity and the elements to extract gold and silver, the geography surrounding the Yankee Girl defied the best railroad surveyors and engineers of the day and no tracks were ever laid

I drove the high altitude 25 mile stretch, 11,000 ft. at the highest, from Silverton to Ouray behind a Colorado Highway Patrol cruiser, keeping me from being overly aggressive. The speed limit was, and no doubt still is, 25 mph because of the steep grades and narrow pavement with no guardrails.

Welcome to 2026! Instructor POV is starting off the new year with one of our own. Karl Vollmer: level 2 sea kayak instructor trainer, advanced river kayak instructor trainer, chair of the PCC (Program Coordination Committee), chair of the river kayak program development committee, database manager, and general paddling powerhouse.

Paddle Canada: Hey Karl, thanks for taking the time to be a part of our Instructor Series. We’re excited to hear all about your experience as a Paddle Canada Instructor so let’s dive right in. Give us an intro about yourself – what do you do and where do you do it?

Karl Vollmer: Thanks, I’ve been in Nova Scotia for almost 20 years now. I have an IT desk job by day, but spend my weekends and evenings on the water, and in the water. I work for Ontario Sea Kayak Center, Cape Lahave Adventures and Cloud 9 Adventures as a sea kayak guide and instructor. My true love is river kayaking. I run https://whitewaterns.ca and https://whitewaternb.ca. I have spent the last 15+ years trying to aggregate and make available all of the river beta and water level information for free to the community as a way to remove barriers to whitewater paddling in the Atlantic provinces. I’ve also recently picked up River SUP’ing which is a new challenge.

PC: What was your first paddling experience and what inspired you to become an instructor?

KV: My first paddling experience in memory is going over a lower overhead dam in a canoe as a small kid with my father. That experience has inspired me to have a better understanding of water and how it works. It has also driven me to help other people understand so that they can be safe, and have an amazing, positive time on the water. Being on the water in a Canoe, or Kayak or on a Sup should be a safe, positive and fun experience. I work as an instructor and guide to help make that happen for people.

Music, the universal language. This is so much fun. Who is the woman in black and grey with the red lipstick? This cover version is better than the original by Romy Madley Croft and Oliver Sim in my opinion. [Click on Full Screen icon in the lower right corner to best appreciate the video]

Where to go? Toward an expansive horizon is always my first choice. In the case of Chaco Canyon Road, the southern exit from Chaco Culture National Historic Park, it was 40+ miles of dirt road across the Navajo Reservation with the warning sign declaring, “Road not maintained, may be impassable to passenger cars.” There are no structures, no signs of habitation the length of that road. There are steep drops into and out of arroyos that flood with cloudbursts, as well as deeply rutted mud slumps that require 4WD to cross even in dry weather. There are no guarantees. But being alone with the unknown is a great way to get to know yourself. [Photo ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on image to enlarge]