A traditional Irish tune that appeared in the Coen Brothers’ film, Inside Llewyn Davis. [Click on Full Screen icon in the lower right corner to best appreciate the video]

All posts by Max Vollmer

Freedom

To laugh is to risk appearing a fool.

To weep is to risk appearing sentimental.

To reach out for another is to risk involvement.

To expose feelings is to risk rejection.

To place your dreams before the crowd is to risk ridicule.

To love is to risk not being loved in return.

To go forward in the face of overwhelming odds is to risk failure.

But risks must be taken because the greatest hazard in life is to risk nothing. The person who risks nothing does nothing, has nothing, is nothing. He may avoid suffering and sorrow, but he cannot learn, feel, change, grow or love. Chained by his certitudes, he is a slave. He has forfeited his freedom. Only a person who takes risks is free.

– Anonymous

Mary’s Peak – Benton County, OR

Truth

The saying, “The truth hurts,” is familiar to almost everyone. But how many people realize that we should welcome having our eyes opened. Prejudice dies, knowledge grows, wounds are healed, danger is averted. Living with the truth leads us to a greater understanding of ourselves and others.

Winding Down

My trip by train across Canada was a long time coming, but it more than met my expectations. What stands out above all is the courtesy, kindness. and generous spirit of Canadians at every turn. This has been the longest visit I have had with Karl since he was a kid at home and Karl, having become a Canadian citizen, mirrors the character of his adopted country.

Foregoing a return by train, I’ll get on a flight tomorrow morning and be back home in Eugene tomorrow night. I have had a wonderful time in Nova Scotia, but there is much that awaits me back home. I am looking forward as always to what lies ahead.

Evening at Duncans Cove

Clouds will bring rain tomorrow, but this evening there was a sunset that looked like the interior of the island was on fire, and a full moon rose at virtually the same time across the harbor. For me, this signified balance and harmony. I spotted the moonrise on the horizon because a tour ship passing in front of Karl’s house caught my attention just as a slice of moon appeared over the water to the east. Can you spot it? [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Maritime Museum – Halifax, N.S.

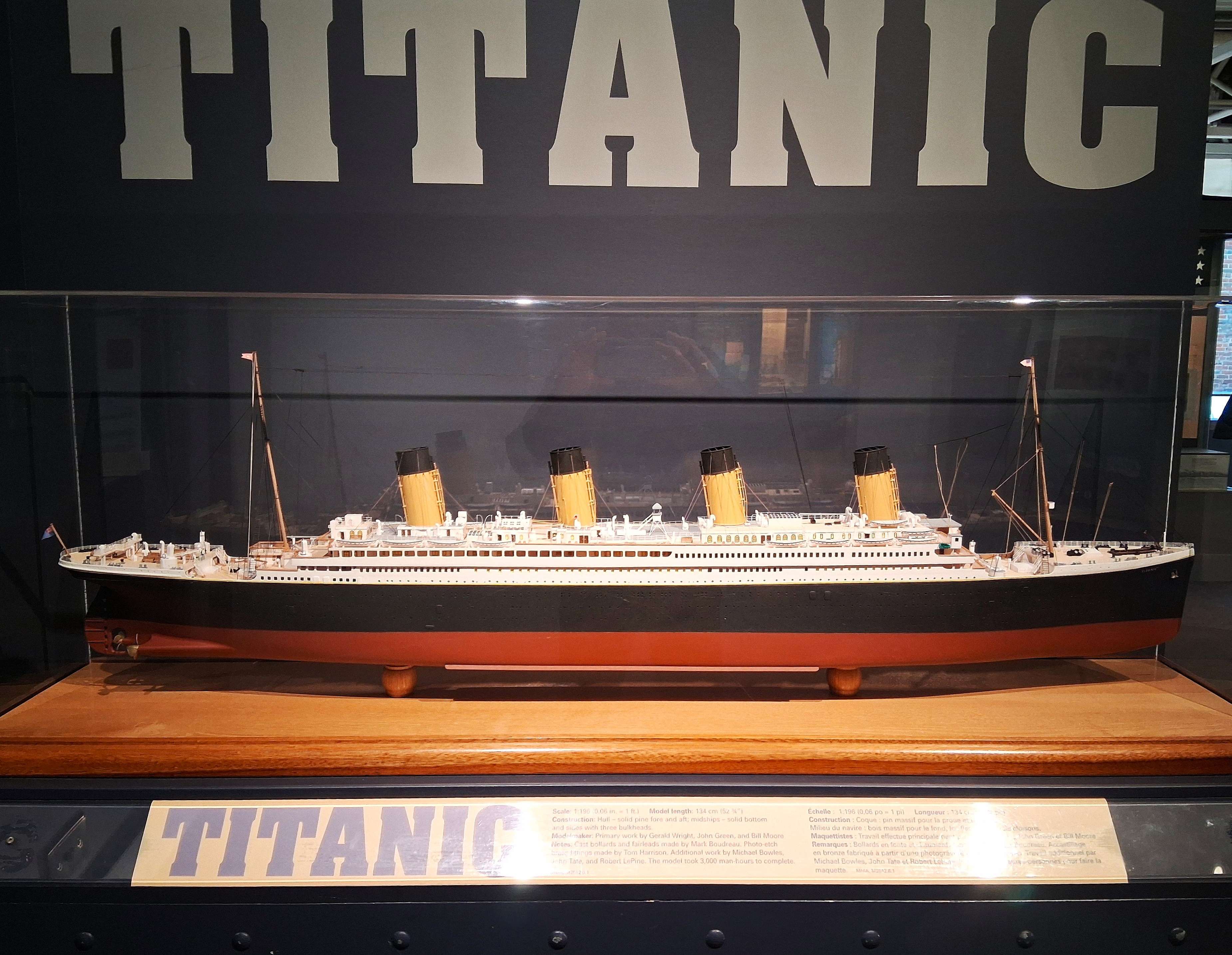

Karl and I visited the Maritime Museum on the downtown waterfront today. It has indoor and outdoor exhibits covering virtually every aspect of travel on the water, from the birch bark canoes made by the indigenous Mi’kmaq people long before the arrival of Europeans, up to and including a scale model of an experimental, armed hydrofoil ship built in Halifax for the Canadian navy. (All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Inside, there are full size examples of small, wood, pleasure and working boats that illustrate differences related purpose and evolution over time.

There are also exquisitely detailed, scale models of ships that served Halifax, like the White Star Lines, Mauritania, that plied the North Atlantic in peace and war. It was built for display in the company’s offices. The model is approx. 6 feet long.

Halifax has a historic connection to the RMS Titanic. Although the ship was built in Belfast, Ireland, when she sank on her maiden voyage, rescue ships from Halifax went out to search for survivors. There are two cemeteries in the city where drowning victims from the disaster are interred. Her sister ship, the RMS Olympic, ferried thousands of Canadian and American troops from Halifax to Europe during WW I using the shortest route across the North Atlantic.

South Coast – LeHave and Lunenberg

The south shore of Nova Scotia is known for its picturesque small towns where fishing is still an important part of local economies, and for its historic buildings, artist galleries, restaurants, surfing beaches and resorts. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

On Sunday, Karl, Stephi and I had dinner at the historic White Point Inn. Beaches there and nearby attract surfers from as far away as Halifax when the waves are good.

I stayed in the Dockside Hotel in Lunenberg Sunday night with a room overlooking the harbor. Lunenberg was founded in 1753 by German immigrants and is known for its lobster fishery and its colorful historic Old Town which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Old Town streets rise steeply from the waterfront. Homes facing the harbor date from the 1700’s and 1800’s. There is no shortage of churches including St. John’s Anglican Church of Canada, founded along with the town in 1753, and built in the second half of the 18th century.

We lost Stan Rogers, Canadian singer songwriter, in 1983 at age 34, but not before he left us memorable songs from the Maritimes. A Stan Rogers music festival is held each year in Halifax in his honor.

Eastern Shore of N.S. – Herrick Cove Fire Station

Drove over to the east shore beaches north of Dartmouth where Karl surfs. Good waves but too much wind, so we stopped at the Rose & Rooster for coffee and brownies. Went a little further to the tiny village of Musquodoboit Harbour (“Musket-dob-it”) about 45 km. from Halifax to turn around and grab some fresh, locally grown produce at Uprooted, the local grocery store. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

On the way back to Halifax we stopped at the Herrick Cove Volunteer Fire Station where my son Karl is the Captain. The station has five salaried career firefighters who are on call 24-7 and twenty four volunteer firefighters who respond to calls as needed.

Engine 60 is only 3~4 months old, cost approx. $750,000, and is the workhorse with the pump that feeds up to four hoses. The captain rides in the right front seat with a driver who does not leave the truck. Four additional firefighters ride in the crew cab where they gear up on the way to a fire. Engine 60 carries oxygen tanks for crew, fire hose, and specialty tools like chain saws, “jaws of life,” etc.

Tanker 60 carries approx. 1200 gal. of water, 1.5 km. of fire hose, and a two ladders, one of which is a 2-flight ladder that will support a fireman in full gear carrying a second person in the case of rescues from upper stories.

Bunks, bathrooms, kitchen, break room, gym, and Karl’s office are on the 2nd floor. There is a traditional fire pole for firefighters to descend quickly from the 2nd floor. You see the Canadian flag along with one with the star, crescent, and red cross that is the Mi’kmaq flag of the indigenous people. Here’s a good place to mention that the Acadians have their own flag which is the French Tricolor with a yellow star in the upper left corner. I see it flown on homes of those who identify as Acadians.

Duncans Cove, Nova Scotia

Karl’s house in Duncans Cove is about 20 minutes from Halifax and adjoins a Provincial Nature Reserve. Fox, bobcat, lynx, mink, weasel, and deer are all native to the area and will occasionally cross the lawn. In the winter months he has the wood stove to supplement electric heat, which makes for a cozy living room. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Spruce trees are sparse on the thin soil and the vegetation is buffeted by strong winds most days of the year.

I hiked across the reserve to the lighthouse in 50 degree weather and then followed the rocks along the shoreline back to the house. Waves were modest today, October 30, but the effects of hurricane Melissa will bring heavy rain, strong winds, and high surf over the next two days, with the peak of the storm expected on Friday.

YESTERDAY, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 29

Karl and I rode the “Harbor Hopper,” a converted WW II amphibious vehicle that took us sightseeing around downtown Halifax and then, being amphibious, drove into the harbor so we could see the city from the water.