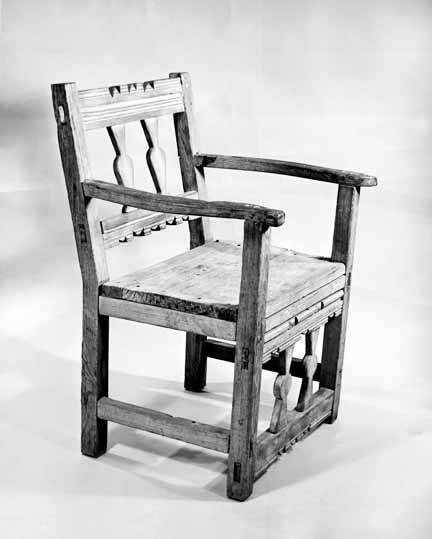

Sidney Barnsley (b.1865-d.1926), was an important and influential Arts and Crafts designer-maker who hand crafted furniture for his family and for clients. He had previously trained as an architect and worked in London before moving to the rural Cotswolds region of England, Pinbury Park and Sapperton in Gloucestershire.

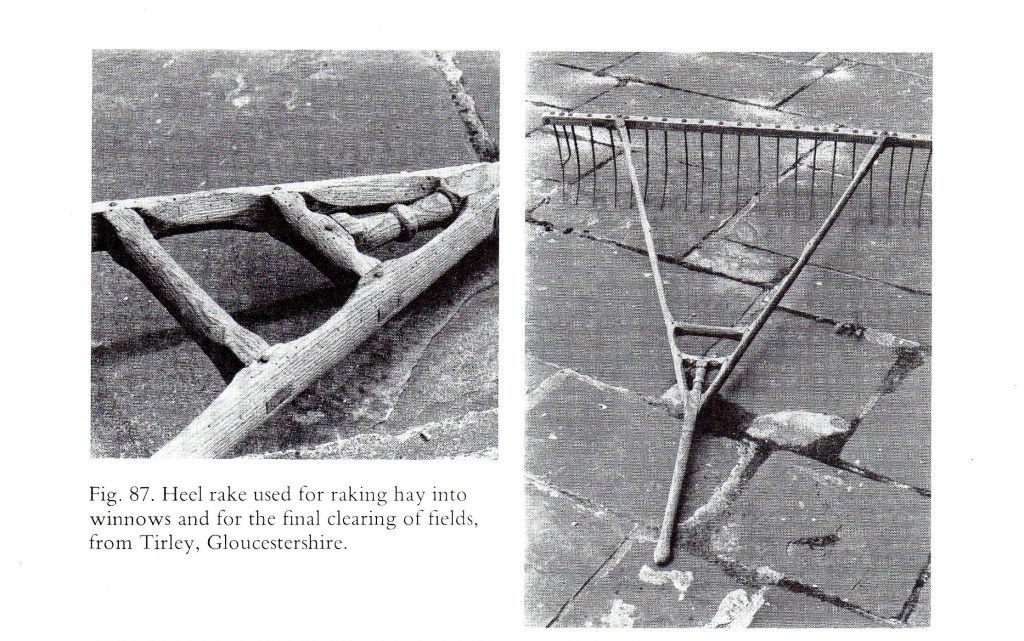

In early 2019, I decided to build an oak dinner table for myself with a leg set that incorporated a “hay rake” or “heel rake” stretcher, a feature that Barnsley had adapted for one of his tables from a traditional wooden rake used by farmers to rake hay in their fields into windrows. Below is a photo of one of these 18th~19th century rakes showing the joinery used to create the handle. It is a marvel of traditional, rural woodworking that is very strong but lightweight . . . a perfect example of form following function. [Click on any image to enlarge.]

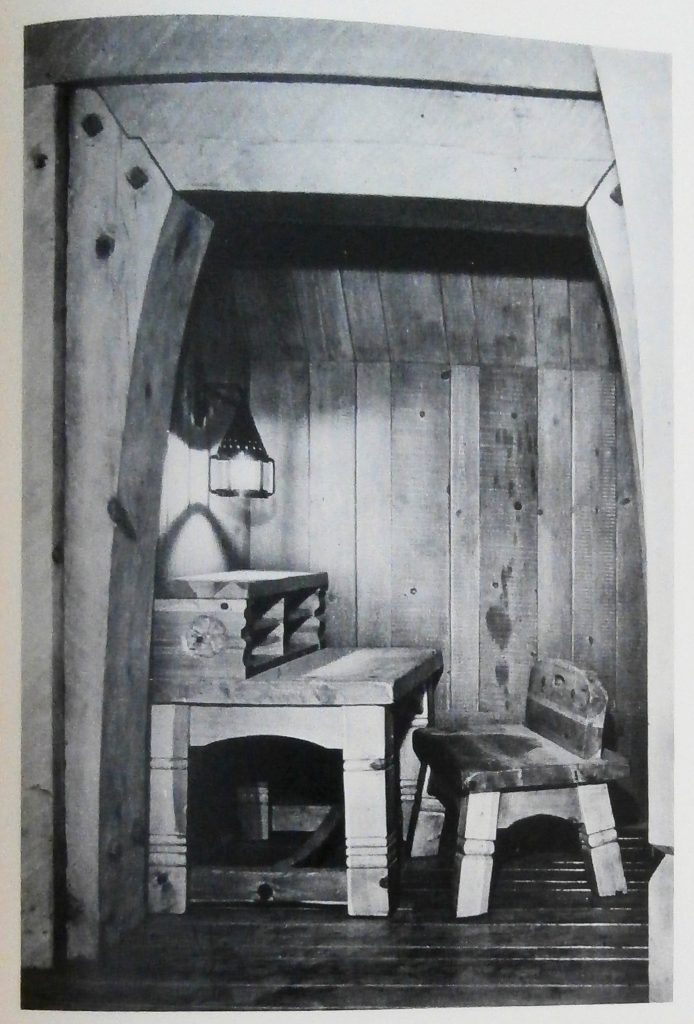

Barnsley used the essentials of the rake joinery to create the stretcher (see below) for his table, circa 1900. All three b&w photos are taken from Gimson and the Barnsleys by Mary Comino (Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., 1980).

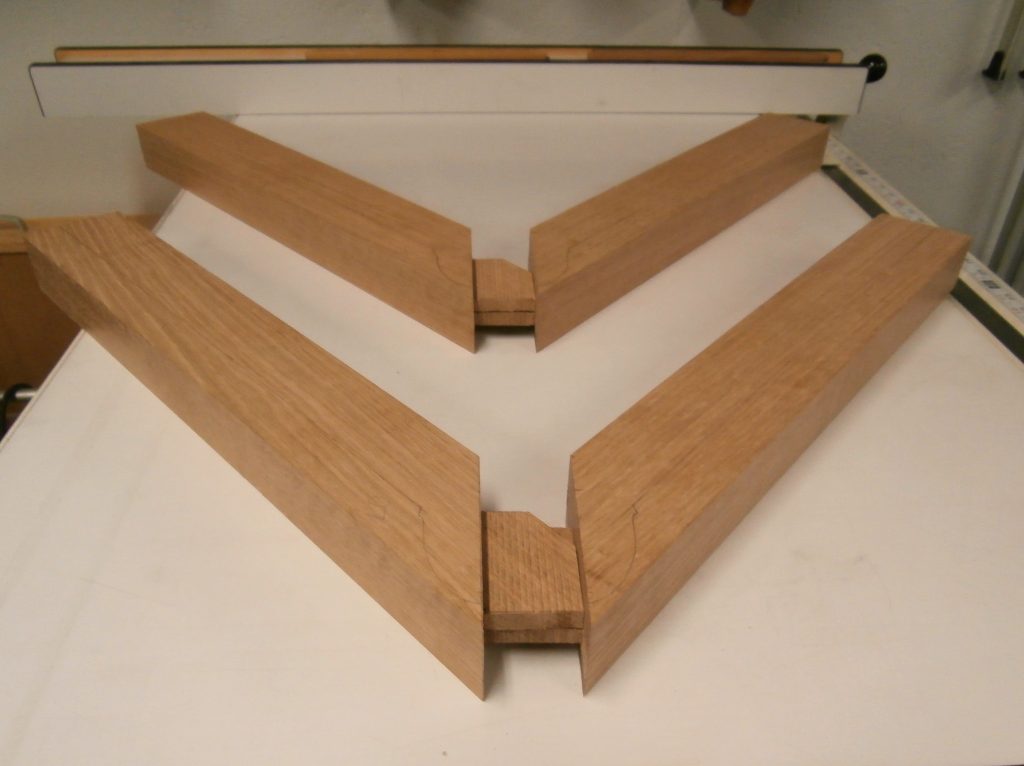

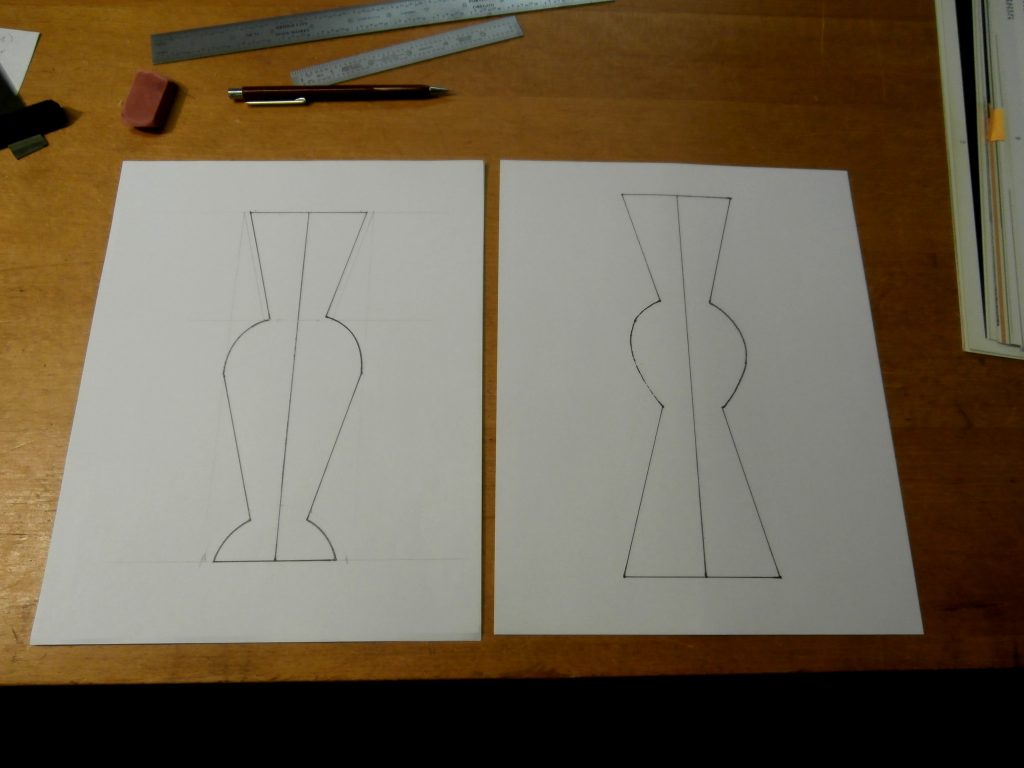

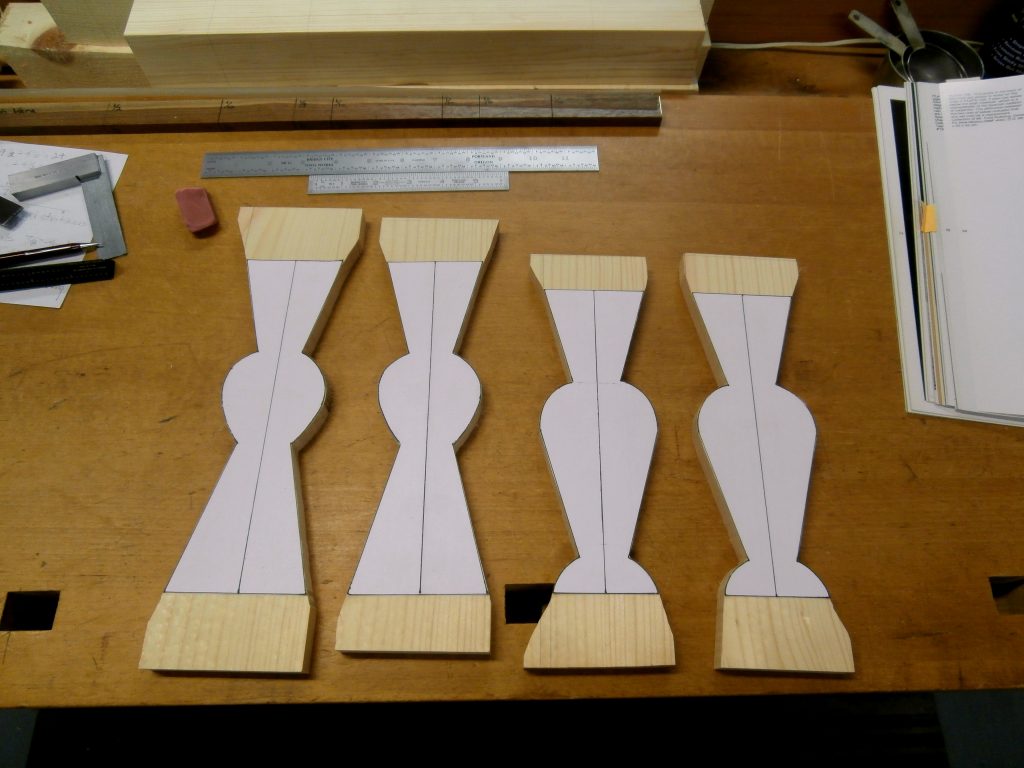

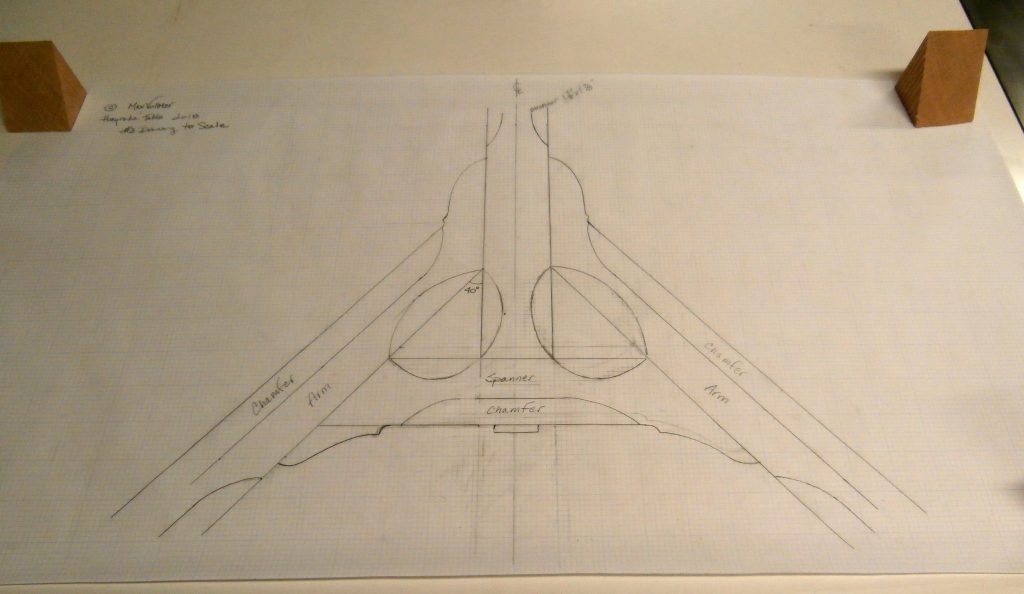

With no original drawings to go by, I made my own full size, scaled plans and set to work on the “Y” shaped joint only to find that my first effort was not going to be satisfactory. It ended up going in my wood stove. I revised the plans based on my experience and started over. [Click on any image to enlarge. All following photos ![]() Max Vollmer]

Max Vollmer]

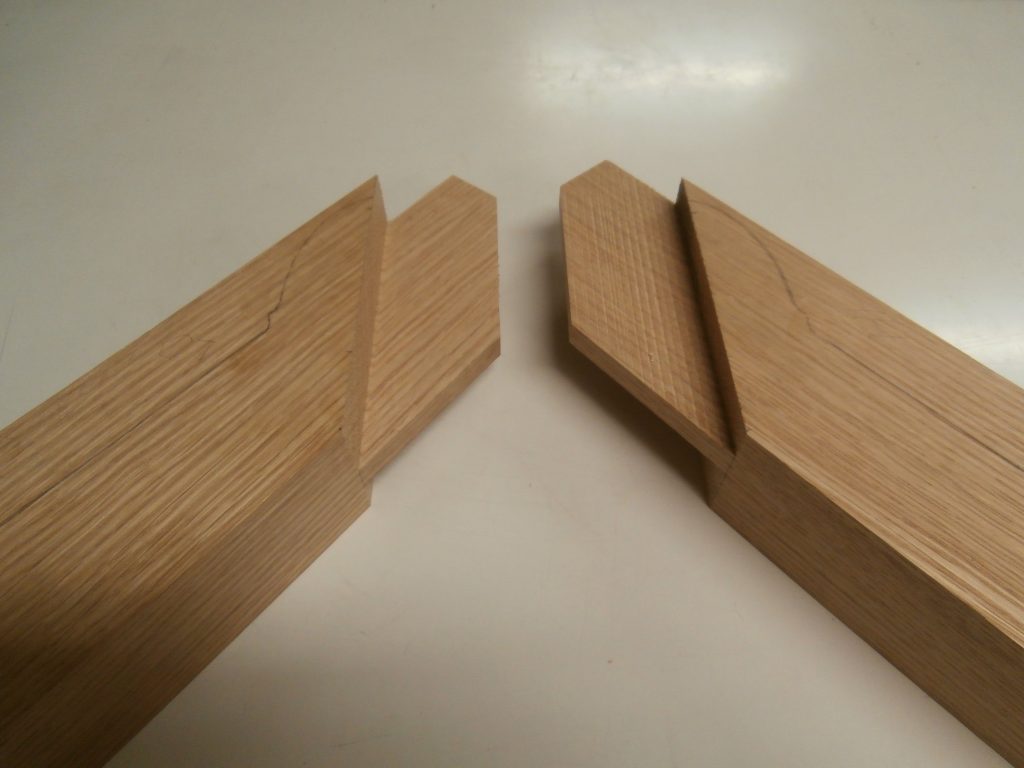

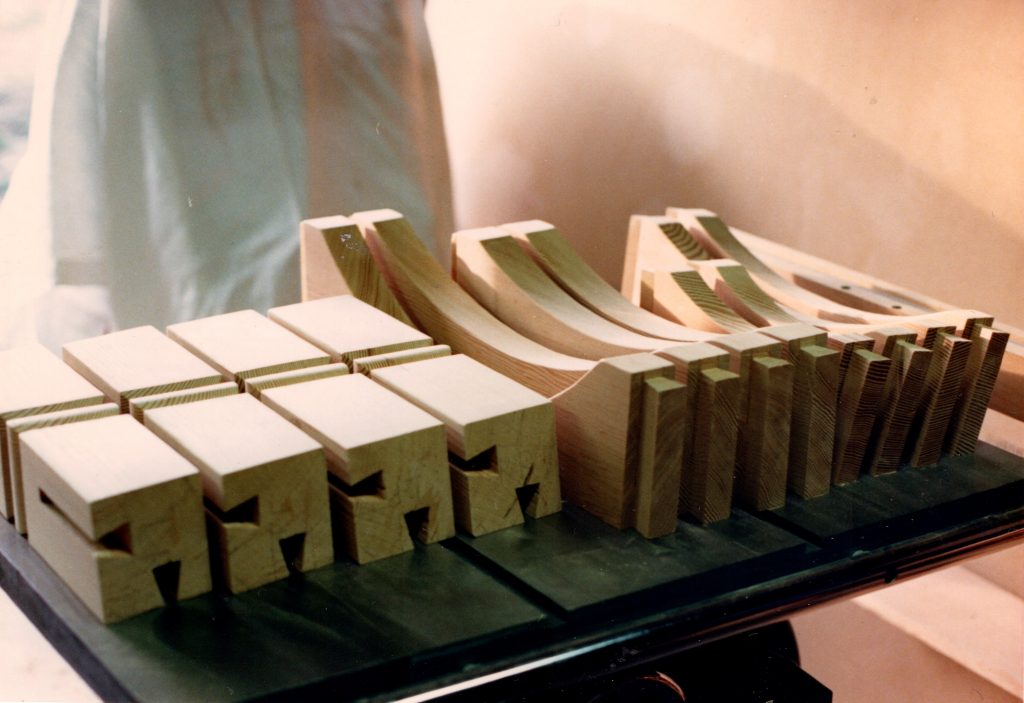

For aesthetic reasons I reduced the acute angle between the arms of the “Y” and the main, longitudinal stretcher from 45 degrees to 40 degrees. I used overlapping tenons on the arms where they intersect and join the main stretcher.

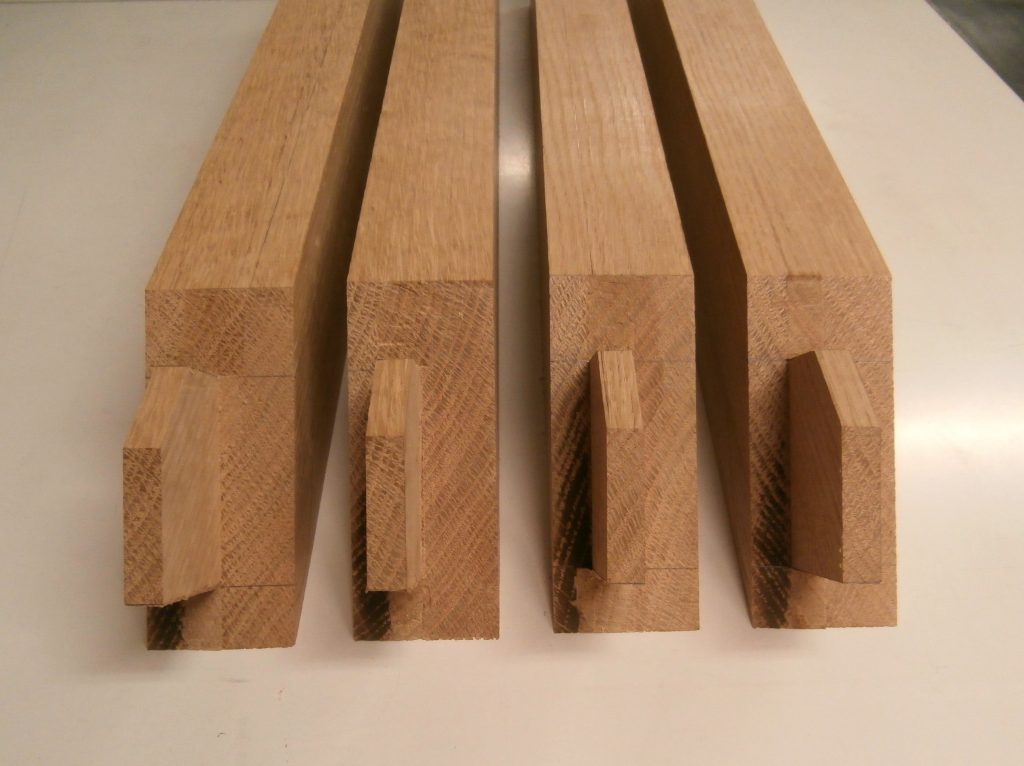

And, based on my first failed effort, I also redesigned the tenons on the “spanner” or brace that connects the two arms of the “Y.” This allowed me to cut “through” mortises in the arms that were perpendicular to the axis of the arms rather than mortises cut at a 40 degree angle. This way I could use straight tenons on the spanner. Not only was this redesign equally strong, it was much easier to cut the mortises. The following series of photos illustrate my approach. [Click on any image to enlarge, All photos ![]() Max Vollmer]

Max Vollmer]

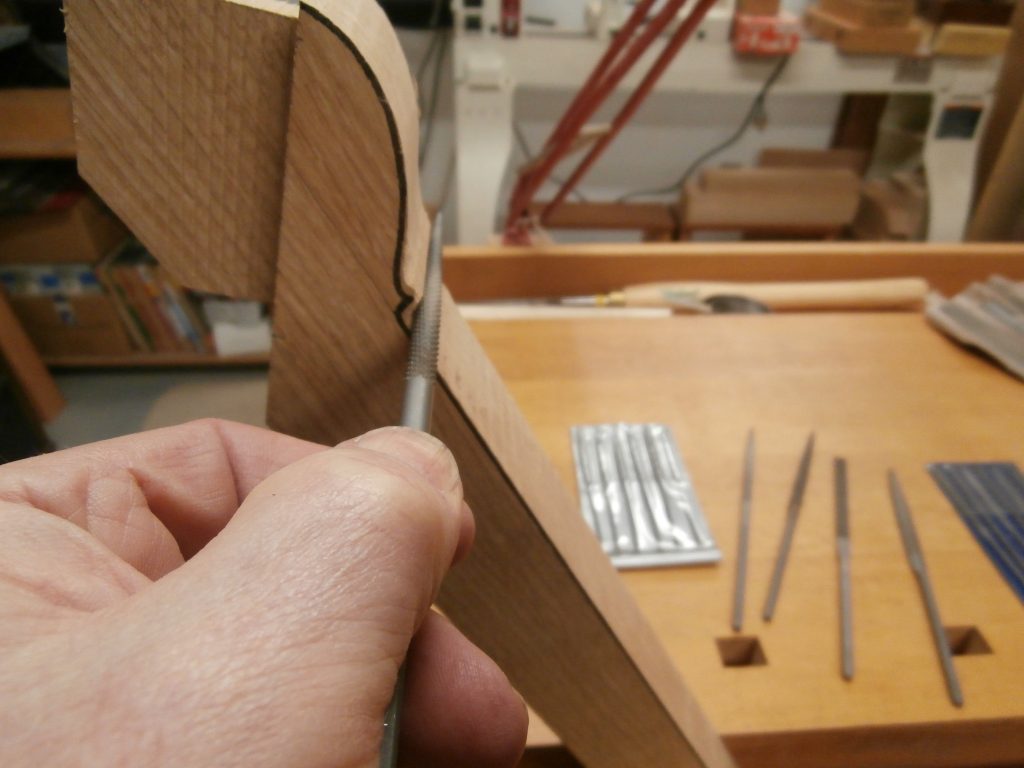

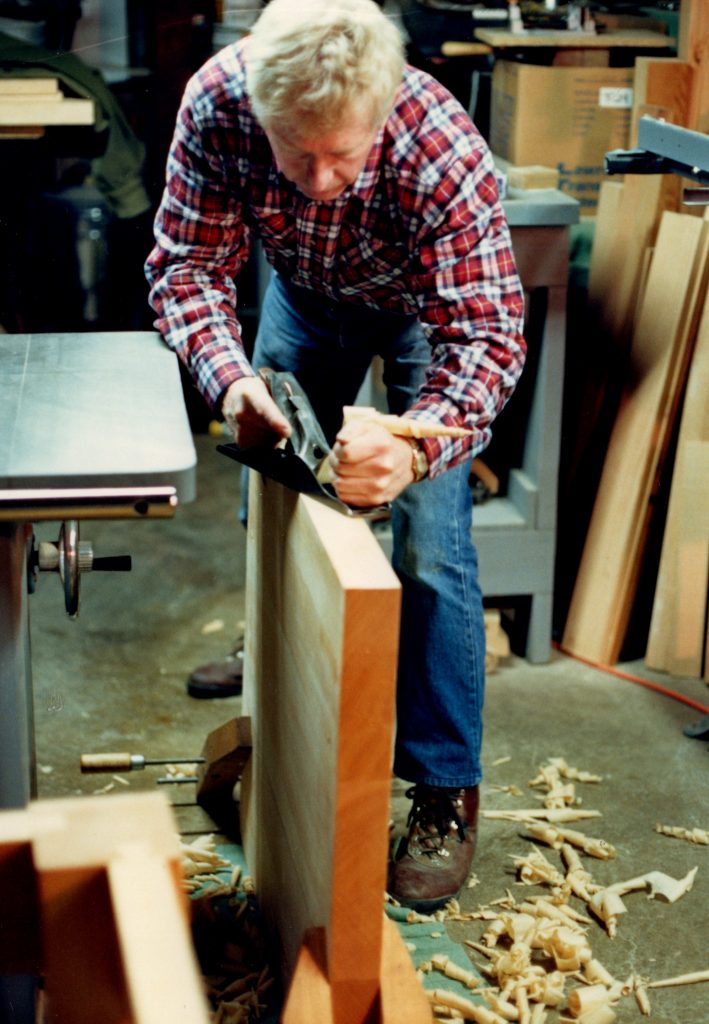

In the next stage, I used a felt tip pen to outline the reduced size of the arms with their curved detailing where the arms meet the long, center stretcher and then used the bandsaw to rough out the shapes. Following that I used an assortment of rasps, files, planes and sandpaper to refine the curved details. The following sequence takes you through the steps. This was a very time consuming process, and one that cannot be duplicated with finesse by any other means. This is what hand work is all about.

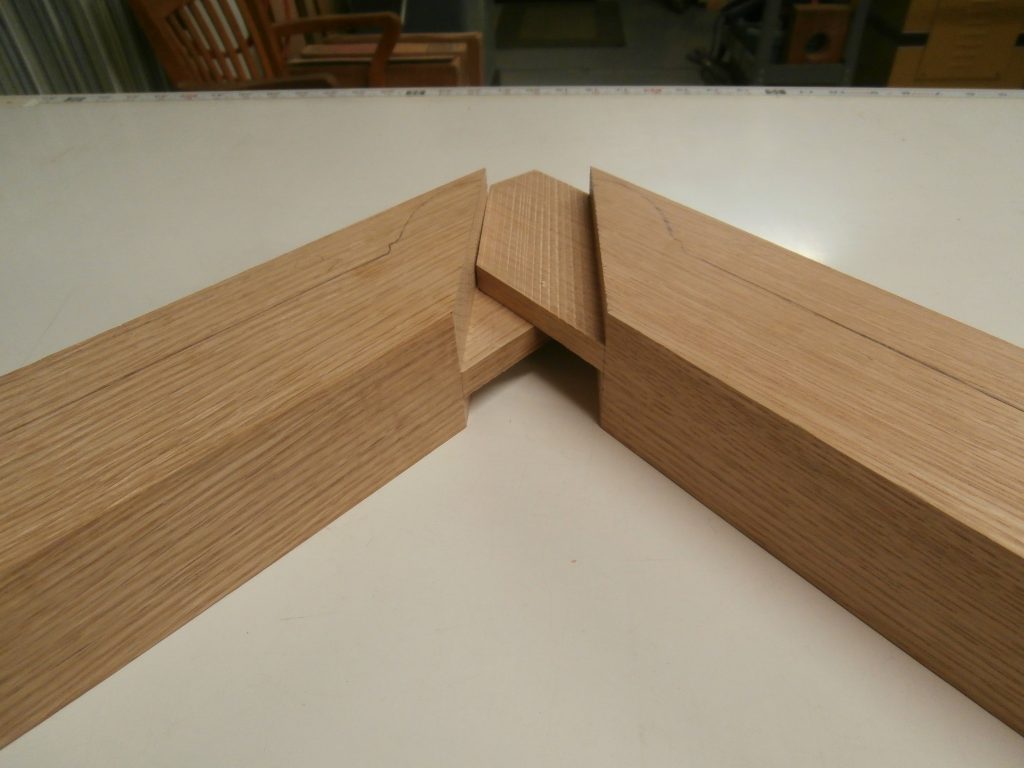

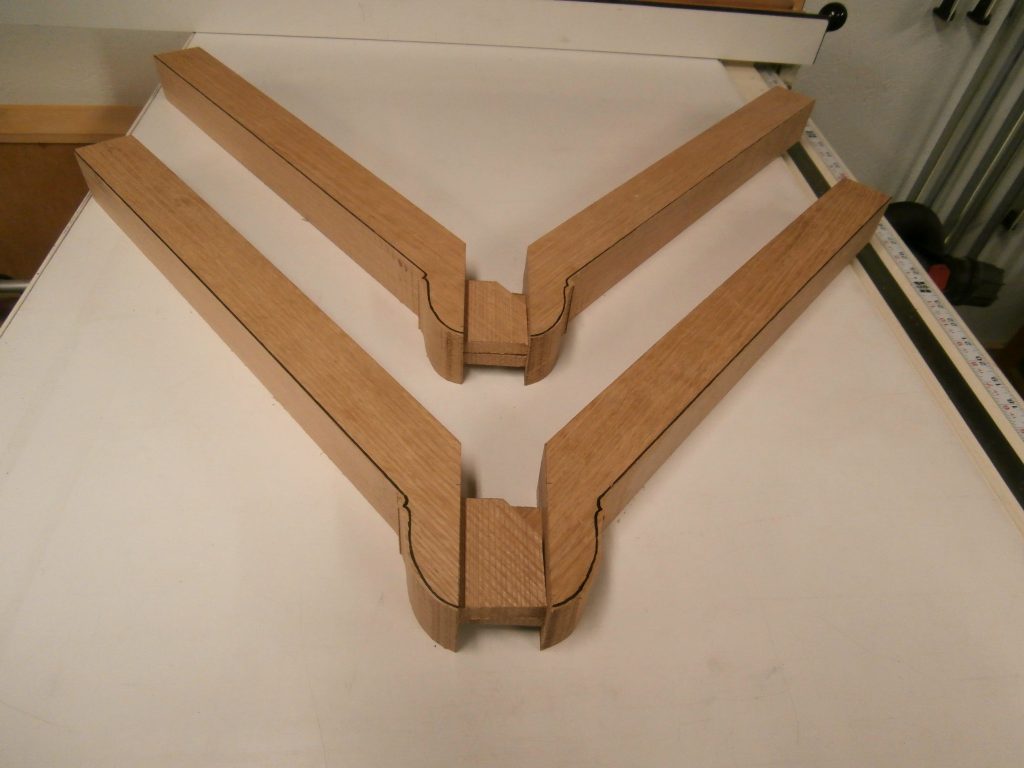

Next I dry fit the arms to the center stretcher to check my clearances. See below.

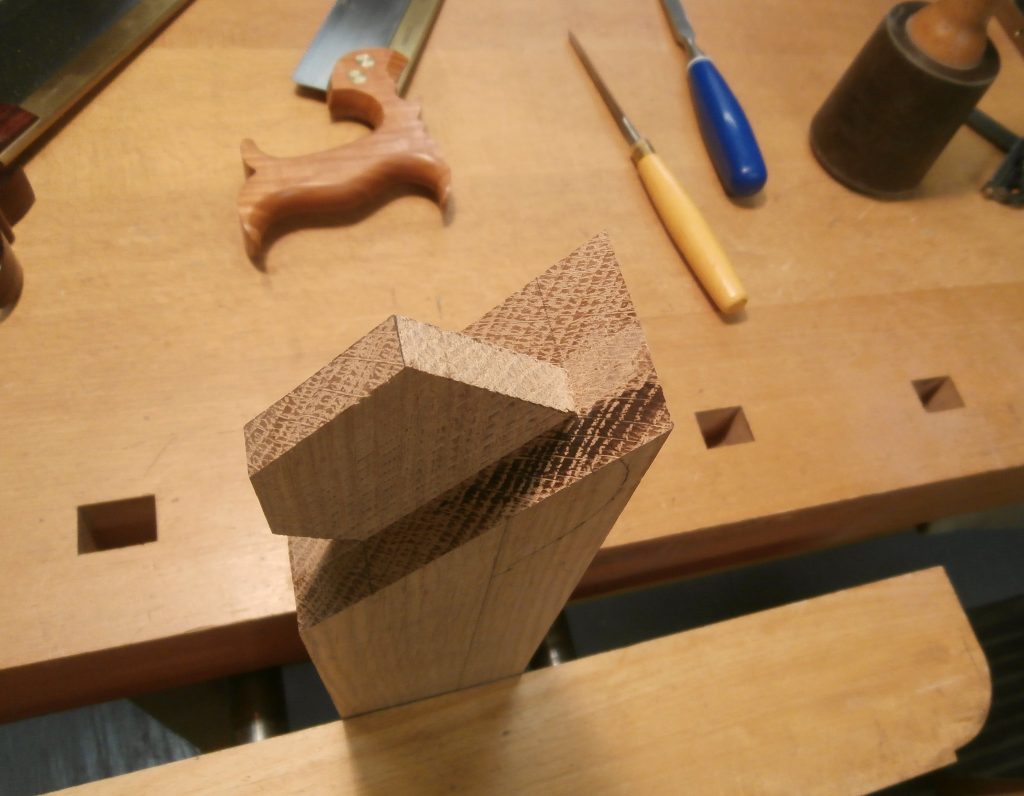

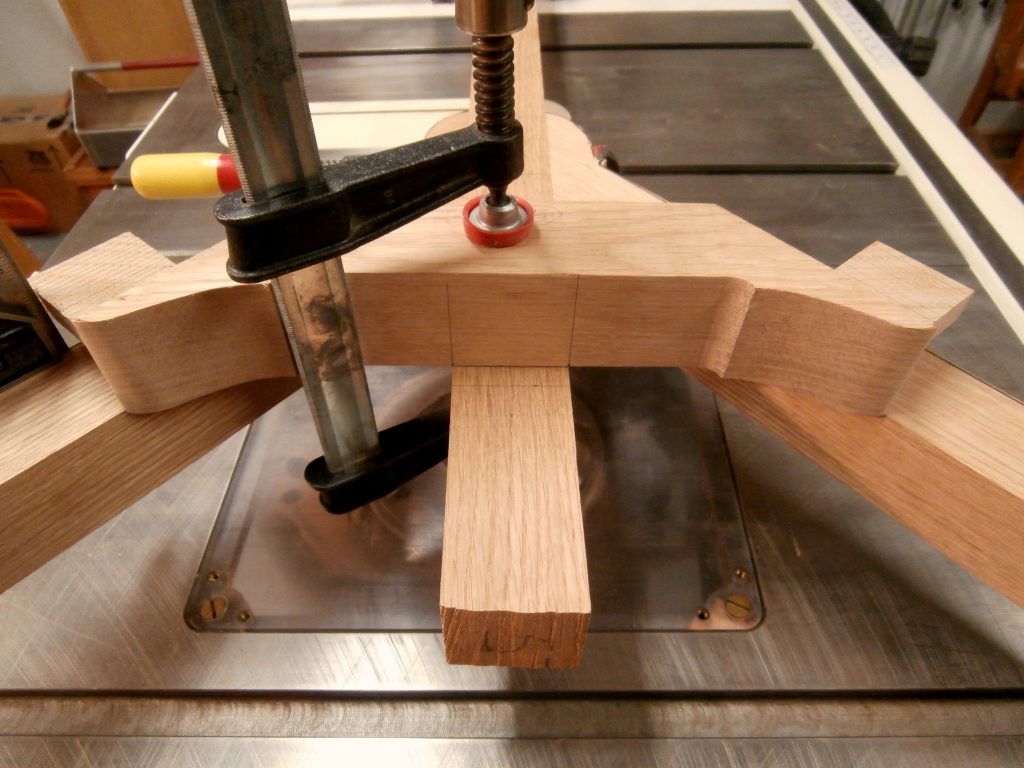

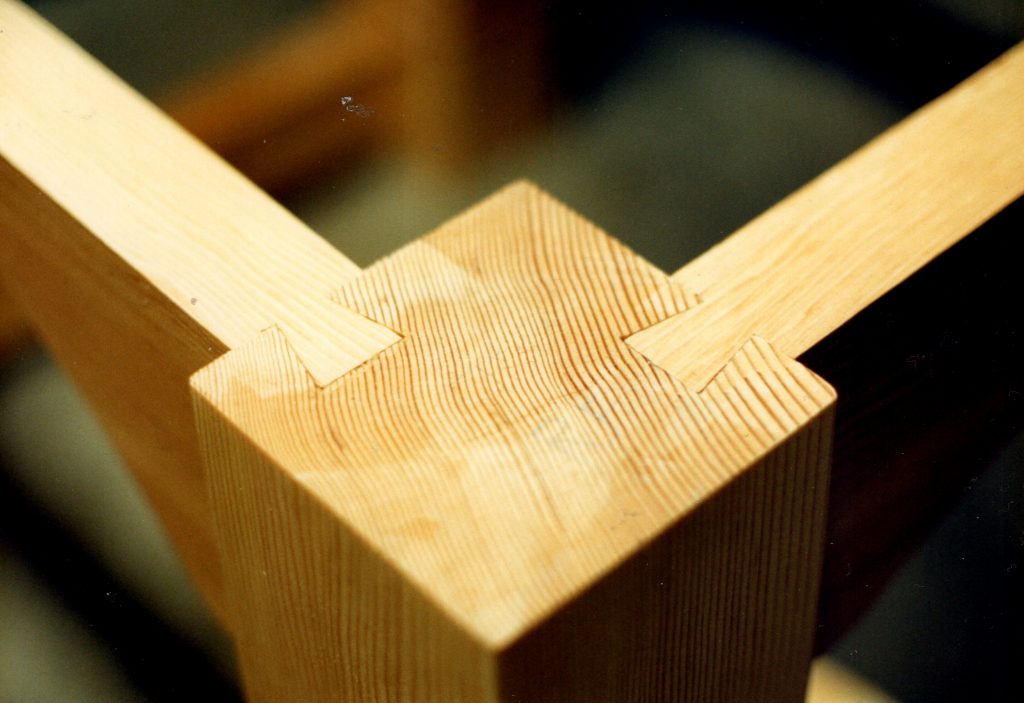

From there I consulted my full size, scaled plans for the spanner that connects the two arms and interlocks with the center stretcher. All measurements, markings, and cuts on the spanner must be extremely precise in order for all four pieces to fit together with tight joints. It is an added challenge to have all the through tenons emerge flawlessly where they are visible on the outside faces. Here is the sequence.

Assembled it looks like this.

The dry fit stretcher assembly is then marked with the location of all chamfers. The chamfers in the original hay rake do not compromise the strength of the rake, but they decrease the weight the farmer has to lift and pull for hours on end. In the table, weight is not a concern but the chamfers add immeasurably to the aesthetic appeal of the stretcher.

See below the full stretcher and leg set ready to go and then assembled. Barnsley chose to have the pegs that lock the tenons in their respective mortises visible from above. I put the pegs in from below so they do not show and therefore do not distract from the flow of the joinery.

Rounding out the table frame, I fit cross pieces to the tops of the legs and then installed two long, under-table supports that are joined to the cross pieces with dovetails. The result is a support structure that, barring fire or natural disaster, has an essentially unlimited lifespan (1,000 years?) if cared for. Here it is with finish and signed with my makers mark on a cross bar.

Here’s the table top. And, following that, the table in my house. Final dimensions are 68″ L x 38″ W x 31.5″ H. The table is compact, but the design of the hay rake stretcher and the canted legs allow for four chairs, across and end to end, and will accommodate four people comfortably for a meal.

I have the lumber to make a long, low, and narrow coffee table with the same hay rake stretcher design, to which I want to add wishbone struts under the table top for added complexity and interest, something Barnsley did in one of his tables. I just need a shop.